Goodbye GAFAM: Block 5 companies at...

09

06

Goodbye GAFAM: Block 5 companies at once → Hell

This experiment of spending time without using GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) products and services, so far I should have stopped using only one company a week , This time, all five companies are blocked at once. What kind of state did reporter Kashmir Hill arrive at after getting out of Hell, who plunged into the life of an almost hermit?

Week 6: All 5 Companies

About 2 months ago, could I live without the 5 big tech companies? We have taken action to answer the question. For five weeks, I blocked Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Apple one at a time, one at a time, to see if I could live a healthy, cultured life without using their products and services. That's right.

To conclude this experiment, I blocked all five GAFAM companies at once.

The experiment doesn't just block visible products, it even cuts off invisible communication with their servers. Using a special network tool made by Mr. Dhruv Mehrotra, we fine-tuned the server with no communication. So I can't open sites that use Google's ads or analytics tools, or sites that use Amazon's cloud/AWS.

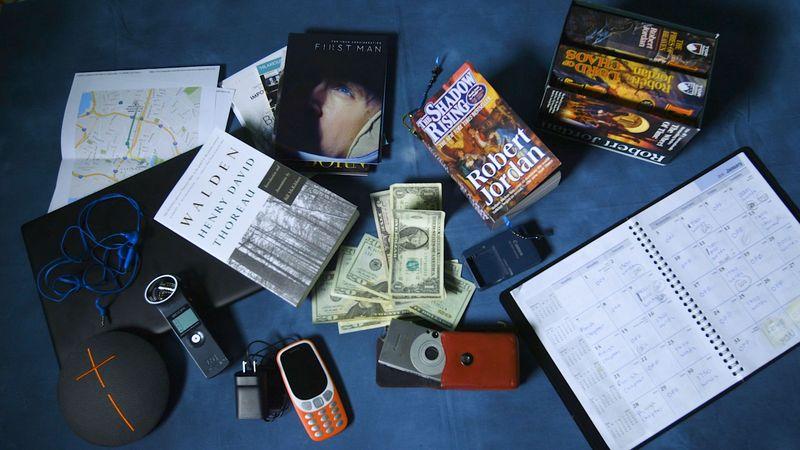

My computer is a special Linux-based one made by a company called Purism, and my phone is a Nokia phone, and I'm trying to learn the nostalgic T9 input again.

I don't think it would have been possible to do all five blocks at once. Just like an alcoholic recovers in 12 stages, I spent five days without using the services of one of the companies, preparing for the final experiment. GAFAM is problematic in terms of data, power concentration, and social control, but it makes our lives much easier.

In the early days of this experiment, I couldn't even remember how to contact people I knew without Big Tech. Google, Apple, and Facebook are moving address books.

So in preparation for the final stage of the experiment, I exported all the contacts I had in Google. Shockingly, the number reached 8,000. I took the 1,500 contacts I had on my iPhone and narrowed them down to 143 that I talk to on a real, regular basis, and put them on my Nokia phone. The number 143 was consistent with Dunbar's number, which is considered appropriate for humans to maintain stable social relationships.

I made a lot of phone calls during the last week of this experiment. Texting on the Nokia numeric keyboard was too frustrating. When I called, the person on the other end of the phone often responded with anxiety after the first call.

On the first day without GAFAM, I couldn't listen to music while driving to work. The car I rented was a Ford Fusion, and the SYNC in-car entertainment system used Microsoft's operating system. In this experiment, you can't use YouTube, Apple Music, or Echo, and you can't use Netflix, Spotify, or Hulu hosted on AWS or Google Cloud, so you can't use background music overall.

This silence made me more dazed than usual. In this state, I sometimes come up with an idea for a half-written zombie novel, or find a theme I want to investigate. But most of the time, I was just thinking about what I had to do.

I can't send huge files!

Many of these things have been made more difficult by experimentation. For example, when I interviewed Alex Goldman of the "Reply All" podcast about Facebook and its privacy issues, the first question that came up was how to record audio.

I live in California and Alex lives in New York. Normally, I would use Skype, but Skype is owned by Microsoft, so I can't use it. So I will talk on the phone and record it with my Zoom recorder. The recording itself was fine, but when I sent the resulting 386MB audio file to Alex, I realized that I had no idea how to send this huge file over the internet.

First of all, I was told that the file size was too large when I tried to send it by ProtonMail or Riseup, which I used instead of Gmail during GAFAM cutoff. The file size limit for these two services is only 25MB. However, not only Google Drive but also Dropbox is on Amazon's AWS, and I use Google to log in, so it's no good during the experiment. Other file sharing sites also use some of GAFAM's web hosting.

Then, should I put it in a USB memory and mail it? I thought so too, but I gave up and called Sean O'Brien, president of Yale Law School's Privacy Lab and advocate for data freedom. He also does marketing for Purism, which makes the computer I got for testing. He's trying to use open source tech instead of tech giants, so I thought he might be able to help.

O'Brien suggested that you first try Send.Firefox.com, an encrypted file sharing service run by Mozilla. However, this service uses Google Cloud, so I couldn't read it from my computer. O'Brien then suggested Share.Riseup.net. It's a file-sharing service by a radical tech group that I use for my personal emails, but it had a file size limit of 50MB.

Solved via the Dark Web

Finally, O'Brien recommended Onionshare, a tool that allows you to secretly exchange files via the Dark Web, which Google doesn't crawl. You need Tor browser to use it. Onionshare was created by my friend Micah Lee, an engineer at The Intercept, so I knew about it. Unfortunately, when I went to Onionshare.org and tried to download the tool, the website failed to load.

When I asked Micah directly, he replied by email, "Oh, yeah." "Now it's hosted on AWS."

The first thing we learned from this experiment was that Amazon's most profitable business was web hosting, not retail. Countless apps and websites use AWS infrastructure, none of which I can use this week.

Micah, why not download it from Github? Github is a subsidiary of Microsoft. O'Brien told me that I could download Onionshare directly from Micah's server using the command line on my Linux computer. Thanks to Mr. O'Brien for teaching me how to do it from scratch, I was able to download it safely at the end.

I set up Onionshare, put the audio files in there, and created a temporary Onion site. I then sent the Onion site URL to Alex so he could download it with his Tor browser. When he downloaded the file I stopped sharing on Onionshare, the Onion site went down and the file disappeared from the web.

(But Alex didn't use this sound in the podcast after all. Ha...)

It doesn't matter if there is an alternative

In the above case, I learned that without GAFAM, just sharing a single file would be a big job. This was how things were going. I mean, there are ways to replace the services of the big tech companies, but it takes a lot of time to find them in the first place, and they're usually hard to use. For example, we ended up using Ask.com (formerly Ask Jeeves) as our search engine. Of course I couldn't use Google, but I couldn't use DuckDuckGo, which is said to be an alternative, because it was hosted on AWS.

That said, I'm not sure if Ask.com is a good alternative. Ask.com is owned by a mega-corporation of over 150 media and dating apps. So all I did was replace a slightly smaller company with a mega-corporation that was trying to monetize user searches.

Surprising joys and sorrows

But there were also unexpectedly pleasant things. I discovered that I could listen to radio on my Nokia, so while I usually listen to Spotify or some kind of podcast or audiobook when I run, I listened to NPR (National Public Radio) during the experiment. I made it Also, I was planning a business trip to South Africa, so it was fun to have a real conversation with the travel agency. Travel agencies are more expensive and less efficient than the Internet, but I couldn't use travel reservation sites, so that was the only way.

The only thing I wasn't happy with was the Nokia 3310's camera, which takes terrible, dark photos. I also have an old Canon point-and-shoot, but I haven't been taking many pictures this week. I don't use Facebook or Instagram, so even if I shoot, I have nowhere to share it.

In some cases, digital alternatives were not found. The person-to-person money transfer Venmo cannot be used without a smartphone, so I paid the babysitter in cash. I started using a paper calendar to manage my schedule. There is Marble instead of the Map app, but the interface was confusing. So I only went to places I knew as much as possible and bought a paper map as a backup.

No, Nokia...

An engineer said that I was talking about how hard it is to drive without a map app.

Gee, the Nokia 3310 was owned by Microsoft!?

We also learned that Microsoft bought Nokia's mobile device division for $7.2 billion in 2014, but two years later it divested its "feature phone assets" for $350 million. 10,000 dollars (about 39 billion yen), and sold it to Foxconn and HMD Global with a poor valuation. Foxconn is famous as an Apple subcontractor, and HMD Global is a company created by a former Nokia executive. HMD Global now sells phones using Nokia's "intellectual property," namely branding. Most "Nokia" phones are Android, but there's also a "classic" line, and the Nokia 3310 is one of them. The OS is FeatureOS made by Foxconn.

So the Nokia 3310 isn't made by GAFAM, but it's definitely close.

Nokia's Digital Health

To find out why HMD Global is still making flip phones, I called Hong Kong-based chief product officer Juho Sarvikas. Saw. According to Sarvikas, HMD Global originally thought that the core market for "classic" phones would be Asia and Africa, where smartphone penetration is low, but it's actually selling surprisingly well in the US.

“Digital health is clearly a field right now,” he said. “When you want to go into detox mode or want to connect less than usual, we want to be a company that provides tools for such users.”

“So this phone is like a nicotine patch for smartphone addiction,” I say.

He laughs and says, "I never thought of it that way, but it sure does."

I thought this phone was aimed at parents who wanted their kids to have a phone without access to social media or apps. "That's true," says Sarvikas.

The idea of digital veganism

Many people I spoke to about this experiment said it was similar to digital veganism. Digital vegetarians reject certain technologies as "unethical." They're scrutinizing the products they use and the data they use and share. They believe that information is power, and that a handful of companies are increasingly likely to have it all.

When I met Daniel Kahn Gillmor, an engineer at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and a full-time lifestyle practitioner, I was surprised to find out that he's actually a vegan. did not. However, I was surprised at how thoroughly he rejected GAFAM. He didn't even own a cell phone and paid as much as possible in cash.

Gillmor said in chat: The chat tool at this time is Jitsi, an open source video conferencing service that can be used with any web browser. There are no dedicated apps to download and no account creation required.

Gillmor runs his own mail server and doesn't use most social media. The only exceptions are Github and Sourceforge, because he's an open source developer and shares his code with others. He calls joining social networks "bait" to lure others into "surveillance traps."

Gillmor says that the flow of information is becoming more and more controlled by companies, and believes that people's lives will be better if such companies can't analyze data and turn it into money.

“I can afford to make this choice. Mr. Miss. "I don't want to sound like I'm criticizing people who don't make the same choices that I do."

The Cost of Vegetarianism

There are indeed costs to making this choice. "The structure of things dictates the choices we can make socially," Gillmor says. "For example, not accepting invitations to parties [on Facebook] because you've decided to get out of the surveillance economy."

Gillmor teaches a course on "digital hygiene" in which she tries to make participants think about their own privacy and security. He usually starts the class by asking students when they think their smartphones are communicating with cell towers.

"Once the data is out there, it can be abused in ways we never expected."

It's not a question of individual behavior

Gillmor says the problem is not an individual problem and should "think of it as a collective action problem, just like environmental problems." increase.

Gillmor hopes that politicians who are legislators will participate, but he believes that technical support is also possible. That means promoting compatible systems, like phone numbers and email addresses. You can call anyone and you don't have to use the same mobile operator as the person you're calling. And thanks to the enactment of the law, it is now possible to keep using the same phone number even if you change mobile carriers.

When companies don't lock users into their own ecosystems, we have more freedom. But that means Pinterest users can register for events notified on Facebook while they're on Pinterest. Apple allows Apple users to FaceTime Android users.

No company that locks you in will give you the keys.

Amazon cut off → I can't receive messages!

Blocking Amazon has been the hardest part for me.

For example, when my friend Katie came from New York. We made a dinner appointment at a restaurant near my house one night. I put it on my paper calendar. The morning of our meeting, I received an email from Katie on my Riseup account. The title is "What's going on?"

Katie has been texting me on Signal for days, but I haven't received it. Because Signal is hosted on AWS. Since Katie didn't reply from me, she sent an email to my Gmail asking, "Did you get a message?" It is up to you to send an email to your Riseup account.

I replied to Katie that I had plans for dinner. But this incident reminded me of the cost of not using GAFAM. Even if I was able to opt out, others may not know I made that choice, or may forget about it.

I had asked my husband to quit GAFAM, but he refused, saying, "I have a real job." I asked him what he finds most difficult about being off GAFAM. "I don't know if they will reply to your text messages," he replied.

"What?" I ask back. "Didn't you answer anything?"

"I sent some messages to Signal," my husband says. He forgot that I'm not using Signal right now.

Let's talk to people more than before

Gafam discontinuation is a conversation topic, and even if it's not, I talk to people more than usual. Because I can't look at my phone when I'm busy in a crowded place.

A professor at a prestigious university said he regularly uses a Google blocker. He said, "I had to disable it when I went to pay my taxes because the IRS website used Google Analytics." It was kind of scary, he said. rice field.

People under the age of 35 were curious about life without smartphones, and were even jealous at times. People over the age of 35 had a nostalgic reaction.

One night I ran into Brewster Kahle, the founder of the Internet Archive, and he was delighted when I told him about the experiment. He told an episode like this.

I'm Not Going To Cut Tech All Out

Sometimes we choose to incorporate technology into our lives, but sometimes technology is forced upon us. TV makers turn their products into surveillance machines, collecting data on what we see, don't see, and in some cases, what we say. Most of TV is getting to that point now.

This week, I stopped watching TV altogether. We don't have a cable TV contract, and Internet TV is not available due to the GAFAM cutoff. I didn't mean to turn "GAFAM cut" into "technology cut", but it actually happened against my will.

In this regard, the current state of the smartphone market is the most unsatisfactory. I would love to use a non-GAFAM smartphone, but that kind of thing doesn't exist as a product right now. Now it's available only to those tech savvy and skilled at installing custom operating systems on specialized devices. However, Eelo and Purism are planning to commercialize this soon.

GAFAM Criticism Blasts

I used to think that idealistic projects like this were bound to fail. But recently, there seems to be a growing awareness of the dystopias created by giant tech. Criticism of GAFAM is pouring out here and there.

For example, a writer friend of mine wrote this commentary in the New York Times. She said, "You hate Amazon? Then try living without Amazon." CNBC's tech reporter says he hasn't used Facebook or Instagram in three months and that it has made him "happier." A CBS reporter tried unsuccessfully to stop using Google. A Vice reporter went without using GAFAM in its entirety for a month (not as exhaustively as I am). The New York Times wrote about an app that tracks a user's location with horrific constant granularity.

Big Tech laid out all of the basic infrastructure for buying and selling our data. They forced us to write public profiles, carry tracking devices in our pockets, and download apps that siphon off our data.

A congressman from California asked.

Doubts about Surveillance Capitalism

These questions haunt society as a whole. Big tech companies have long been revered for making the world more connected, information more accessible, and transactions easier and cheaper. Now they are suddenly the target of anger. The reason is that they facilitated the spread of propaganda and falsehoods, made us dangerously dependent on their services, and turned our private information into the currency of a surveillance economy.

The world is flawed, and the calls to hold tech giants to account, right or wrong, are growing louder by the day.

As Harvard Business School Professor Shoshana Zuboff argues in her new book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: By analyzing and processing data to the extreme and trying to turn it into profit, a total surveillance society is inevitable, and that is what drives our economy.

Zuboff's public relations person sent me a new copy of the book as an e-book, and I read it with interest, but I can't read it because I can't use my Kindle this week. Instead I read the paper book, Henry Thoreau's Walden: Life in the Woods. By the way, I ordered this book from Barnes & Noble, the last large-scale bookstore chain in the United States. And this book is full of messages about returning to nature and not being indulged in the lies of modern society.

But this book was published in 1854, so it wasn't smartphones or screens, but jobs and newspapers that people were told to keep away from.

Anger at Profit-Driven Smartness

I called Open Markets Institute Fellow Lina Khan about what governments could do. She has been noted (at least in the academic world) for her papers on the need to regulate Amazon's monopoly.

Khan is working on further papers as a fellow at Columbia University in New York. Khan is neither an Amazon Prime member nor does he use Gmail. I was planning to interview her over the phone, but just before that, I saw a tweet from a woman who works as a video producer for the Washington Post. The woman wrote an open letter to a tech company after being bombarded with baby-related ads after experiencing a stillbirth.

Her appeal also reminds us of the dangers of privacy.

I mentioned this at the beginning of my phone call with Khan and said that this anger was growing.

Yes, says Khan.

Should the government intervene soon?

Khan believes that judicial intervention is needed to prevent monopoly tech companies from acting anti-competitively. In the 90s, authorities intervened against Microsoft.

"Some of the big tech companies have bought out their rivals and killed them," Khan points out. In a recent email leaked from within Facebook, CEO Mark Zuckerberg endorsed blocking access to Facebook's social graph from (then-competitor) Vine.

Europe has already moved on, with Google fined and Facebook banned from integrating data with WhatsApp and Instagram without user consent. But US antitrust law enforcement officials didn't touch the tech companies. Tech companies' services are cheap or free because that's a good thing for consumers, a state that authorities want to promote. But what if the "consumer" was the company's product?

Will Internet = Free also change?

An uncomfortable thought has been running through my mind this week. If we can escape the economy of monopoly and surveillance, we may need to reconsider the idea that everything on the Internet is free.

So when I tried to create a fourth folder in ProtonMail and was told that I would have to upgrade from free to paid for it, I decided to pay €48 per year. In return, I get a 5GB email account, whose contents cannot be scanned or exchanged for money.

But I also know that not everyone can afford to pay $50 for something that is free and easily available. So if the world were to go that way, the rich would be able to maintain their privacy online, while the poor (and vulnerable) would have their data taken advantage of.

Tech and Children

Last week, my 1-year-old daughter Ellev described Alexa as 'scary' and 'creepy', a concept she learned at Halloween. became. I don't know what that feeling is. It's uncomfortable for a small child, or for anyone, to have an incorporeal voice always there and listening.

But this week, Ellev kept crying because he wanted to use Alexa. In my house, I can't listen to songs like "Baby Shark," which my kids love, but through Alexa. She said, "I don't want Alexa," and I felt guilty for depriving my daughter of it and for making such a young child dependent on AI.

On the last day of the GAFAM cut, my family flew from the West Coast to New York, and my husband begged me to stop the experiment a day early so he could show Ellev his iPad. . But I was adamant to maintain this condition even after a 6-hour flight.

"I'm the only one who'll switch seats away," he warned jokingly.

My husband charged his iPad in case my willpower faltered, but I was determined. I read to Ellev, played with a magnetic drawing board, sang songs, and spent at least an hour playing with "Wizzle sticks," the sticky and bendable sticks that used to come in Alaska Airlines snack packs. . My daughter slept for the last hour and a half of the flight, but with the iPad she usually doesn't sleep.

This was Ellev's 26th flight, and in the cab after landing, my husband told me it was the easiest flight.

Technology creates problems that technology can solve

We arrived at the Airbnb in Brooklyn that we had booked months in advance (Airbnb is hosted on AWS). , is strictly NG). There was a locked box outside my apartment and I opened it with a four digit PIN. Enter the building using the key that entered there, and the room key will open with the same 4-digit number. I don't have access to the Airbnb website, so I had the apartment's address and 4-digit number on a piece of paper.

We went in without a problem, and since we were hungry, we went to the restaurant we had just seen from the taxi. After that we needed to buy some ingredients, but Ellev was exhausted so I went back to the Airbnb and her husband went shopping. I used the key to enter the building, but after climbing the stairs to the 4th floor where my room was, I realized that there was no paper with the PIN number on it. I didn't even memorize the number.

Ellev cries and tries to turn the doorknob. I started feeling the panic I used to feel when my kids were younger, and more recently that feeling when your phone battery is about to die.

My computer was supposed to be in a locked room. I use a password manager on my computer and use it for all my online accounts. So even if I quit GAFAM right now, I can't even log into Airbnb on another computer.

The masochistic part of my brain whispers that I'm in this situation because I used an AWS hosted site. It would have been nice to have booked a regular hotel over the phone. If so, the solution is to get a new key card. Technology creates problems that technology can solve, and vice versa.

While soothing Ellev, I tried several four-digit numbers from my vague memory. One of them was a hit. As soon as I went inside, I connected my iPhone to the charger and was relieved that I could use it again from tomorrow.

It's almost impossible not to use it, but there are things you can do

When you criticize tech companies, it's easy to say, "If you don't like it, don't use it." I did this experiment to see if "I don't want to use it" is possible. And it turned out that it wasn't possible. Apple was the only exception. The graph below shows the number of requests my device made to each company's server this week.

The reason we use GAFAM is because they control the infrastructure of the internet, online commerce, and the flow of information. Many of them are very good at tracking users on the web, even when they aren't using their product or service directly. In the early days, they may have sold books, provided search tools, and showcased pretty girls on campus, but today they're much more powerful and involved in almost everything you do online. is. They look like modern day monopolies.

After the experiment, I started using the GAFAM service again, but not as much as before. As a consumer, I began to look for alternatives as much as possible so that I would not encourage their monopoly.

What does tech mean to me?

But the experiment meant more to me. This time, I was forced to reexamine the role of technology in my life. This experiment helped me break free from the modern addiction of swiping my phone to pass the time, allowing me to engage in conversations with others and seek stimulation from the real world.

I removed time-wasting apps like Words With Friends and Hearts. I don't even look at Instagram as much as I used to, to the point where when a friend tags me in a story, I don't see it within 24 hours, so it disappears.

I turned off my phone around 9pm every night and didn't turn it on until I really needed it the next day. It took me two weeks of using a "nicotine patch" Nokia flip phone to get there, but eventually, I no longer had the urge to reach for my phone by my bed to start my day every morning.

According to my iPhone's weekly "Screen Time" report, my time on the iPhone has plummeted to less than two hours a day. The iPhone is no longer a "part of your body," but more of a tool you use when you need it. I still use Google Maps and Waze when I'm in a strange place, I text my friends and family far away, I share pretty pictures on Instagram, but I put my iPhone away when I don't need it. I was able to obtain such power again.

To the Slow Internet

My experiment is the digital version of the juice cleanse. I'd rather stay "healthy" after the fact than most dieters, but I'm not going to be a digital vegetarian. I cherish the "slow internet" lifestyle and try to be more discerning about the technology I incorporate into my life and what motivates the companies that make it. Big tech is changing the way the world works, for better or worse, but we can choose the good and reject the bad.

I asked my husband if anything had changed since I quit GAFAM.

"You lost track of time," he jokes, but it's true. I only look at my phone occasionally and I don't have a clock around. Personal devices have made watches obsolete. I'm more focused on the moment, but I don't know what time it is.

The solution to this is simple. I should buy a watch. Not smart, of course.

The Goodbye GAFAM series so far

Goodbye GAFAM: Trying to stop Amazon → It was impossible

I really can't do this. Do you know GAFAM? G: Google, A: Apple, F: Facebook, A: Amazon, M...

https://www.gizmodo.jp/2019/01/i-tried-to-block-amazon-from-my-life-it-was-impossible.html

Goodbye GAFAM: I'm super lonely after quitting Facebook...

Do you know GAFAM? G: Google, A: Apple, F: Facebook, A: Amazon, M: Microsoft...

https://www.gizmodo.jp/2019/02/i-cut-facebook-out-of-my-life-surprisingly-i-missed.html

Goodbye GAFAM: Try to quit Google → Internet collapse

Cut off Net Five Elders GAFAM, 3rd week is Google. Week 3: Google "Don't be evil" disappeared Google "Don't be ...

https://www.gizmodo.jp/2019/02/i-cut-google-out-of-my-life-it-screwed-up-everything.html

Goodbye GAFAM: Quit Microsoft → Huh? Can not?

Series 4, which cuts off the 5 giant dragons GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) that dominate the web, now...

https://www.gizmodo.jp/2019/02/i-cut-microsoft-out-of-my-life-or-so-i-thought.html

Sayonara GAFAM: I'm quitting Apple → I feel like a part of my body has been ripped off

This plan is to refuse products and services of Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, and Apple for one week each. Week 5...

https://www.gizmodo.jp/2019/02/i-cut-apple-out-of-my-life-it-was-devastating.html